Interview with Franco Maria Ricci a year before his passing in September, 2020.

JW. What are some of your favorite pieces from your own collection?

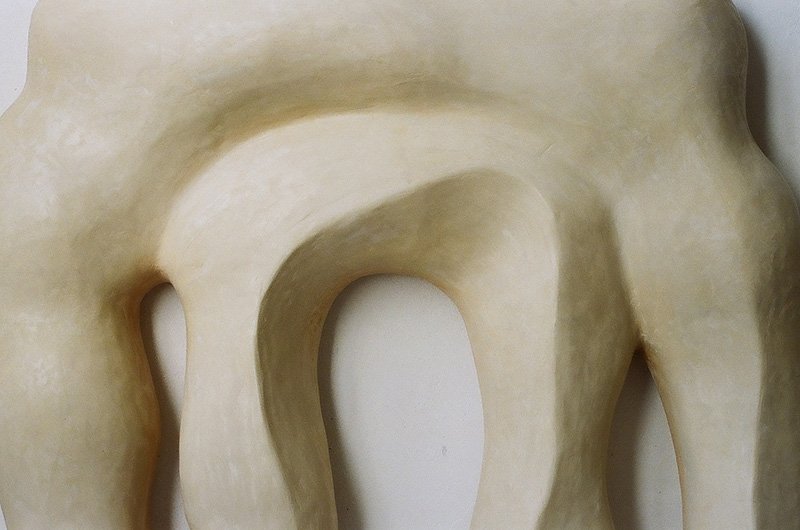

FMR. One of my favorites is the Vir Temporis Acti, made by the Milanese sculptor Adolfo Wildt (1868-1931) between 1910 and 1912 for his friend and patron Franz Rose.

I love that the supreme smoothness of the surfaces aims at an idea of the incorporeal, of stone against the light.

Wildt did not believe in Naturalism, and he pursued it as a challenge. Also, the surprisingly attractive wax models by Francesco Orso portraying Victor Amadeus III of Savoy and of his wife Maria Antonia of the House of Bourbon. This wax sculptor, who was active in the second half of the 18th century, and skilled at rendering a disturbing sort of hyper-realism, is the emblematic expression of my eclectic collecting preferences.

There’s a section of paintings upstairs that seem to all have the theme of mortality (skulls, scrolls, epitaphs, memento mori), how did you find these artifacts and why did you keep them?

I was still a young man when I first became attracted to these themes [of mortality], constant in art.

I was always wandering around art fairs, like the one in Maastricht or the one in Parma, always looking for them in the catalogs of the main auction houses.

My purpose was to form a Wunderkammer, a place born to arouse wonder. Wonder, but also a feeling of unease owing to the many symbolic representations linked to the fragility of life of the so-called Vanitas.

Did you originally purpose your Labyrinth to be a museum for people to visit?

When the labyrinth project was born, it was a private matter. I wanted to leave something of myself to the land that had nourished and enriched my family; like the gentleman Vicino Orsini, who translated his solitary fantasies into the Park of Monsters in Bomarzo, or Vespasiano Gonzaga, who died in Sabbioneta, in the heart of his unfinished dream made of stone.

As time passed, that initial idea was, for the most part, transformed. Now, I’ve come to think of my enterprise above all as a legacy—as a way of giving back to the Po Valley, which includes Parma, and to its countryside and nearby cities.

Tell me about where the idea for the maze came from.

It was tortuous and unpredictable, originated from encounters, experiences, emotions, and thoughts, which, at some point, flowed together into one project.

Caverns were probably the first labyrinthine structures human beings came into contact with, in a distant past. And I, too, rummaged through my own past, finding a version of myself as the guise of a young amateur speleologist, equipped with the right clothes, flashlights, ropes, and climbing-irons. I was a second-year student at the Faculty of Geology and, with some friends, I had founded a so-called Cavern Society. My weekdays moved along on the surface, in the sunlight, while my weekends were usually devoted to the dark bowels of the earth.

I want to recall another experience… one that goes even farther back, as it dates to my childhood. Once in a while, gypsy men and women wearing long colored skirts would come to Parma with their caravans. They would (as the story goes) install a mirror labyrinth. I was filled with awe.

The fact that at a certain point, much later, those laborious paths re-emerged, as if from a sort of oblivion, and began to attract my attention was first because of my readings, and then because of my meeting and befriending Jorge Luis Borges.

The paths the hesitant steps of this blind man drew in spaces that were easy and familiar reminded me of the uncertainties of those who move amidst forks in the road and enigmas.

My project was consolidated in the 1990s.

Borges had died by then, when I met Davide Dutto, a young Turin-born architecture student. Dutto suggested an intriguing publishing project, which I took up enthusiastically. The idea was to reconstruct, with new software, the Island of Cythera, the place described in the most precious of printed books, the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, published by Aldus Manutius in 1499 in Venice.

Thanks to a computer and to Dutto, who knew how to use it, the Volume Il Giardino di Polifilo portrayed some striking images of that enchanted and imaginary place. The images Dutto succeeded in making on a computer reminded me of the labyrinth and the vague idea I had been toying with while talking to Borges of actually building one. I asked Dutto for his help and we got down to work.

Then there was another labyrinth, a more difficult, more intricate one: all the paperwork needed to be able to start building. There were two other stages: preparing a realistic and feasible site plan for this labyrinth, that was different from the first ones I had worked on; and planning the buildings that would occupy the center and surrounding area to house an art collection and library.

For the Labyrinth, I again asked Dutto for his help and for the actual construction I turned to a Parma-based architect who is famous internationally and rather close to me thanks to his Neoclassical taste and outlook: Pier Carlo Bontempi.

And the pyramid, at the end? In a way, it felt like a kind of temple for me.

For the pyramid, and for all the buildings, I turned to the great architects who lived during the French Revolution: Boullée, Ledoux, Lequeu, but also the Italian architect Antolini, who presented Napoleon with a visionary project for the Foro Bonaparte in Milan.

Undoubtedly due to circumstances, none of these men have left us with great buildings; however, drawings and projects, dictated by a love of geometry, Egypt, the Greek and Roman world, and a visionary talent, nurtured by the Utopias of the age in which they lived, remind us that neoclassicism was not the classical, but, rather, fertile ground for the modern. That repertoire of shapes continues to serve as models for a new architecture, the knowing heir to a long past.

The pyramid is meant to be a chapel, even if it’s not sacred yet. And there is a labyrinth on the floor, just like in the French medieval cathedral, as a symbol of faith and as a reminder of the tortuous path that every man has to walk through to reach Eternal Deliverance.

Text by Franco Maria Ricci and John Hudson White

4. SEPTEMBER. MMXXV. PLUM

SUBSCRIBE,

SAVE,

LIKE (6),

SHARE: COPY PERMALINK